Since the beginning of June 2024, France’s political system has been experiencing a phase of strong turbulence. The storm started on June 8 and 9 with the European Parliament elections and reached its apex with the snap legislative elections that took place in two rounds on June 30 and July 7. Within the space of barely one month, France – and the rest of the world – witnessed a massive surge of the far right. This was followed by a successful effort to contain that surge and the unexpected success of a left-wing coalition. This political roller coaster is the result of several factors. First, discontent among French voters in relation to president Macron and his policies played a major role in determining the results of the European elections. Second, the different electoral systems that France uses to elect its European and national members of parliament played a major role in influencing the two elections. Then the outcome of the national election was swayed by the organizational and political dynamics that have characterized the various parties and coalitions that populate France’s political landscape.

On the European election days, French voters – just like all voters in the 27 countries that make up the European Union – were called to elect their representatives in the European Parliament, one of the legislative bodies of the European Union. The total number of European Members of Parliaments (MPs) is 720, and each member state elects a number of MPs that tends to be proportional to the size of its population. In this case, French voters were called to elect 81 of the 720 members of the European Parliament. The electoral system for the European Parliament has to be proportional representation in each and every country of the EU, and in France voters elect their MPs through a proportional electoral system with blocked lists.

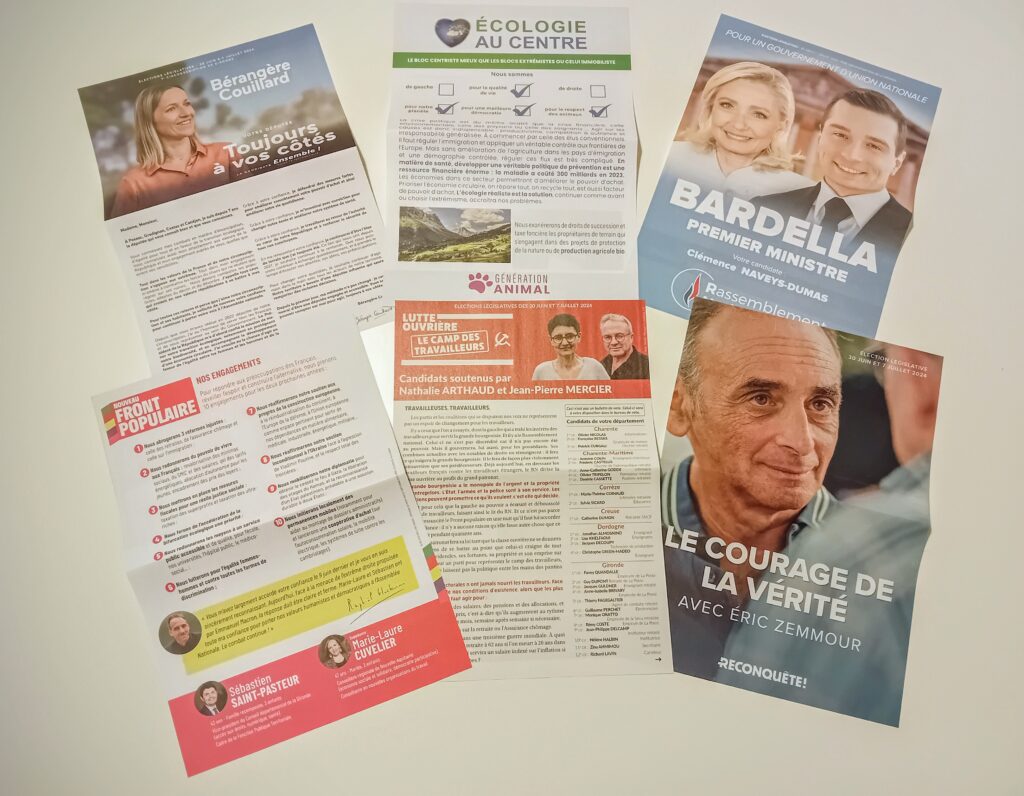

France approached this election with a delicate domestic political situation. President Emmanuel Macron was weakened by the fact that his coalition did not have an absolute majority in the National Assembly (or Assemblée Nationale, the most important house in France’s bicameral parliament). Moreover, the president’s popularity had been severely hit by a series of unpopular reforms (such as retirement and immigration), domestic social and political crises, and a suboptimal rate of GDP growth. The European Parliament election thus became an opportunity for French voters to express their disappointment. The parties of the left faced the electoral contest running solo – although loosely gathered on the national level under the umbrella of a coalition called NUPES (Nouvelle Union Populaire Écologique et Sociale). In this situation, the far right National Rally (Rassemblement National), boosted by the rising star of the new party president, Jordan Bardella, and the charismatic figure of Marine Le Pen, found itself in the best position to capitalize on popular discontent.

The National Rally thus dominated the European election, obtaining 31.4% of the vote and 30 seats out of the 81 European Parliament seats awarded in France. Macron’s European coalition, Renew, came a distant second with 14.6% and 13 seats – the same number of seats obtained by the center-left coalition Réveiller l’Europe with 13.8% of the vote. The populist left party La France Insoumise (France Unbowed) won 9 seats with 9.9% of the vote.

Although the European elections are by no means formally tied to the national political scene, the poor result of the pro-Macron coalition convinced the president to exercise his constitutional power to dissolve the National Assembly and hold a snap election (the next national parliamentary election in France was scheduled for 2027). Such a bold and risky decision might have been determined by several political calculations on Macron’s part. He might have tried to mobilize his base – and the French electorate in general – with the expectation of motivating voters to turn out en masse to support him against the National Rally. Alternatively, he might have calculated that had the National Rally won a parliamentary majority almost 3 years before the presidential election, the far right’s popularity would have been diminished by the frustrating challenge of cohabitation – a situation of divided government in which a president and a parliamentary majority from different parties must govern together.

The electoral system for the National Assembly is very different from the one used for the European Parliament election. When they vote to elect their representatives to the 577-seat National Assembly, the French use a first-past-the-post system articulated in two rounds. Candidates from French parties run in every district, but unless a candidate obtains an absolute majority in the district in the first round, only those who pass a 12.5% threshold make it to the runoff. This usually means that in the second round only two candidates face each other. The supporters of the candidates who did not pass the first round must decide whether to abstain or vote for the remaining candidate they consider the most compatible with their preferences – a logic that is expressed in the formula “in the first round, you choose; in the second round, you eliminate.” Three- or four-candidate runoffs – known as triangulaires or quadrangulaires – are technically possible but in general quite rare.

The delicate political situation and the logic of the national electoral system had an important impact on both the voters and the parties. The June-July parliamentary election campaign was the shortest since 1958, but the high stakes stimulated a surge in participation, which reached 66.63% in the second round, the highest turnout since 1997. The snap election and the surge of the far right also favored the formation of the Nouveau Front Populaire (New Popular Front). The NFP is a new leftist coalition featuring the Socialist Party, the Greens, the Communist Party, and La France Insoumise. The name is a reference to the Popular Front that won the 1936 French elections and formed a government led by the Socialist Léon Blum.

The National Rally took the lead in the first round with 33.3% of the vote, but only 76 seats were awarded to the party in this phase of the election. The hastily-assembled NFP surprisingly came a close second with 28.6%, while Macron’s coalition, Ensemble!, came a more distant third with 20.9%. This phase of the election turned out to be extremely contested, with a record high number of triangulaires – 306 – and even some quadrangulaires. Such a result played in favor of the opponents of National Rally, and stimulated the creation of a “Republican Front” between the NFP and Macron’s coalition in the second round. The NFP instructed their candidates to withdraw from triangulaires if that helped defeat the National Rally candidates. The leadership of Macron’s movement did not take such an explicit pledge, but many candidates stepped down as well, and the result was a reduction of the number of triangulaires to 89 – a development that strengthened the “Republican Front” and disadvantaged the National Rally. The second round thus overturned the results of the first one. The NFP came first with 32.6% and obtained 188 seats – La France Insoumise was the most voted party in the coalition, closely followed by the Socialist Party. Macron’s Ensemble! came second with 27.9% and 161 seats, while National Rally finished third with 24.6% and 142 seats.

Since no party or coalition has won the 289 seats necessary to obtain an absolute majority in the National Assembly, any appraisal of the results of France’s latest electoral contest is inevitably subject to debate. It seems nonetheless possible to approach the question of who gained and lost. The election turned out to be a debacle for the National Rally, which came third in a race that appeared to have already been won. However, the National Rally actually increased the number of seats in the National Assembly from 89 to 142 and consolidated its position in already strong districts – small cities and rural areas, especially in the southeast, north, and northeast of France. The party, moreover, now dominates the French right. The more mainstream center right formation – Les Republicans – only won 39 seats, and its platform as well as its rhetoric are becoming less and less differentiated from that of the National Rally. Jordan Bardella’s reputation was hit by the debacle, but the new president of the National Rally is quite young and his political career may be long – while Marine Le Pen might still have a shot in the 2027 presidential election. It is also important to observe, however, that the National Rally failed to break out of its traditional strongholds and that the party appears to be at its strongest when it can be seen as the only meaningful alternative to the status quo – as demonstrated in the early June European elections. When French voters are presented with an alternative to the National Rally’s extreme right heritage and platform, they appear to be inclined to vote for that alternative.

Macron managed to contain, in fact even outperform, the National Rally, but his coalition lost 76 seats. This means that many of his most loyal legislators – who could have kept their seats until 2027 – have been politically “sacrificed” in the president’s effort to recover from the poor performance in the European election. Macron is already in his second presidential mandate, hence he will not be able to stand for reelection in 2027. As these lines are written, the president has an approval rate of only 30% and it is not clear what the future of his movement will be.

The NFP and its success were the surprise of the national election and played a crucial role in containing the surge of the far right. The leftist coalition gave many French voters an appealing alternative, came on top in the national election, and performed very well in the southwest of France and in the country’s big cities. However, the NFP’s chances to consolidate as a major force in France’s political landscape might be undermined by internal differences and disagreements. Jean-Luc Mélenchon- the leader of La France Insoumise and the most recognizable figure in the coalition – is a controversial and divisive politician. He and his party have taken a number of extreme positions – such as expressing support for Vladimir Putin in the context of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine or refusing to clearly condemn the October 7 terrorist attacks perpetrated by Hamas against Israel. That attitude undermines the standing of La France Insoumise and the rest of the coalition as a credible government force, and creates deep cleavages within the NFP. There is thus a serious risk that the coalition might split in the face of the challenge of turning from an emergency electoral formation into a real government force.

The leaders of France’s most important international partners – especially US President Joe Biden and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz – have reacted positively to the election results, and have expressed satisfaction for the successful containment of the far right’s surge. The French election has had a more contradictory impact on international financial markets. The weaker than expected performance of the far right somewhat reassured global investors. The prospect of a hung parliament and the strong performance of the Nouveau Front Populaire, however, have created some concerns. Some of the key economic policies contained in the NFP’s platform might lead to a further deterioration of France’s already concerning budgetary situation and create tension with the European Union. Investors are particularly concerned about plans to raise the minimum wage and undo Macron’s retirement reform, which had raised the age of retirement. It can be argued, however, that the austerity measures implemented by Macron did not sufficiently revive the French economy either, while they contributed to the discontent that favored the rise of the far right in the June European elections.

The scenario produced by France’s June and July 2024 political roller coaster remains uncertain and volatile. A coalition among the heterogeneous parliamentary blocs that have emerged from the national election, or some form of technocratic executive, will be necessary to give France a new government and run the country until at least 2027. This is when the new president will have the opportunity to dissolve the National Assembly again and try to obtain an absolute parliamentary majority. Nonetheless, multiple points are clear. French voters are not prepared to see the far right in power at the national level but are very disappointed with the economic, political, and social direction the country has taken. At the same time, the French are still quite interested in policy proposals that emphasize social justice and an inclusive society. Equally important, they are attracted to an economic model less focused on austerity and more concentrated on the need to stimulate growth and raise living standards. It is now the duty of France’s leaders to come together and give their citizens a stable government that can meet those demands, restoring confidence in the country’s future.

Diego Pagliarulo

Mia Morreale contributed to the editing and proofreading of this article.