Donald Trump’s victory in the 2024 US presidential election is destined to have very significant repercussions for the United States and the world. Although it is still too early for a thorough assessment of the global implications of a second Trump presidency, an analysis of the elections results, the president-elect’s key foreign policy nominations, and other major developments that are defining the trajectory of the Republican party can suggest some important emerging trends that may shape America’s role in the world for the next four years. As far as the Middle East is concerned, the new leadership in Washington is likely to have a significant impact on challenges such as the war between Israel and Hamas, relations between Washington and key Arab partners like Saudi Arabia, and US policy toward Iran. It seems reasonable to expect the transition from the 46th to the 47th US president to bring about some important changes, but also – for better and for worse – to reinforce some existing trends. Moreover, the president’s instinct could be another peculiar “Trump Card,” and may play a crucial role in defining the administration’s Middle East policy.

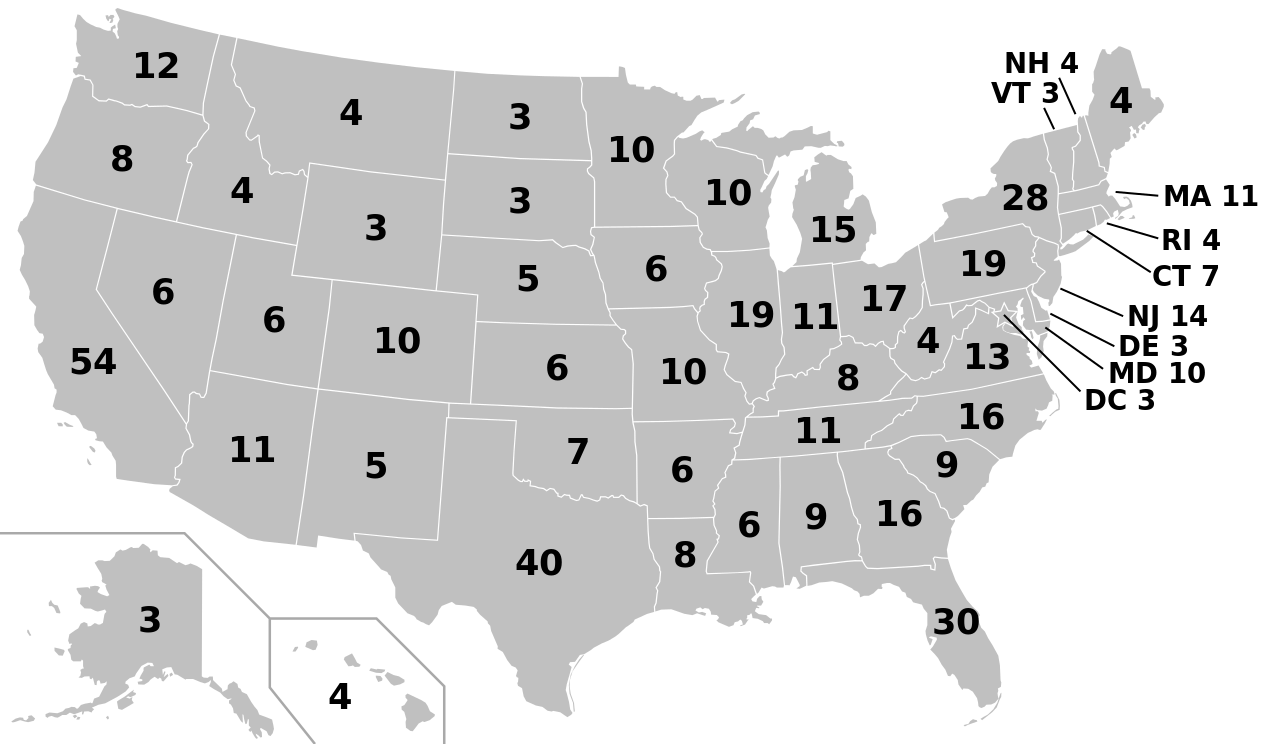

Trump won the 2024 presidential contest by obtaining 312 electoral votes out of 538. The Republican candidate was voted by more than 76 million voters (two million more than in 2020) representing 50 percent of the electorate. In contrast, the Democratic candidate, Kamala Harris, obtained around 73 million votes (48.2 percent) – around 8 million less than the 81 million won by Joe Biden in 2020 (51.3 percent of the popular vote). The substantial decrease in support for the Democrats also shaped the Congressional elections, and gave the Republicans slight majorities in both the Senate and the House of Representatives – 53 out of 100 seats and 218 out of 435 seats respectively, as these lines are written. Hence, the Grand Old Party is set to enjoy a “trifecta” – control of both the White House and the two houses of Congress – while the current configuration of the US Supreme Court is also characterized by a conservative majority. It is reasonable to expect this dominant position on the institutional level to give Trump and his administration significant freedom of maneuver in both domestic and foreign policy. However, it must be observed that in the Senate a 60 votes supermajority is required to pass legislation in several areas that represent major items on the president-elect’s agenda, such as immigration reform and the plan to abolish government departments. The Senate is also the chamber that has exclusive competence in relation to the ratification of treaties and the appointment of top administrative and judicial positions, so Trump will need to take into account the advice and consent of Senators in order to fill the key domestic and foreign policy posts in his administration. It is also worth remembering that in 2026 the entire House of Representatives and one third of the Senate will be renewed. Hence, the configuration of Congress may change halfway through the presidential mandate.

Donald Trump ran an “America First” campaign infused with isolationist rhetoric. Along with a commitment to erect massive tariffs, criticism of the EU and America’s European allies, and a confrontational stance towards China, as a candidate, Trump promised to end the war in Ukraine “in 24 hours” and to bring peace to the Middle East. Isolationism, however, should be considered an attitude rather than an actual foreign policy strategy. It seems more likely that, just like the first Trump presidency (2017-2020), a “Trump 2.0” foreign policy will be unilateralist – skeptical of multilateralism and international institutions while focused on military power rather than diplomacy – but not necessarily disengaged from the world. Moreover, Trump will have to operate through an extensive and complex bureaucratic apparatus and will be surrounded by advisers who will be tasked with the implementation of the president’s vision.

When it comes to foreign policy, America’s conservative camp is in fact segmented into a variety of schools of thought. As noted by Célia Belin, Majda Ruge, and Jeremy Shapiro, the Republican party is divided into different “tribes:” the “restrainers,” the “prioritizers,” and the “primacists.” In relation to America’s policy toward the Middle East, the restrainers call for disengagement, while the prioritizers advocate for relying on local partners, and the “primacists” envision a strong regional role for the United States. All Republican “tribes” seem opposed to the prospect of negotiating with Iran, but the prioritizers are also inclined to support a “maximum pressure” approach towards the Tehran regime, while the “primacists” are prepared to use military action.

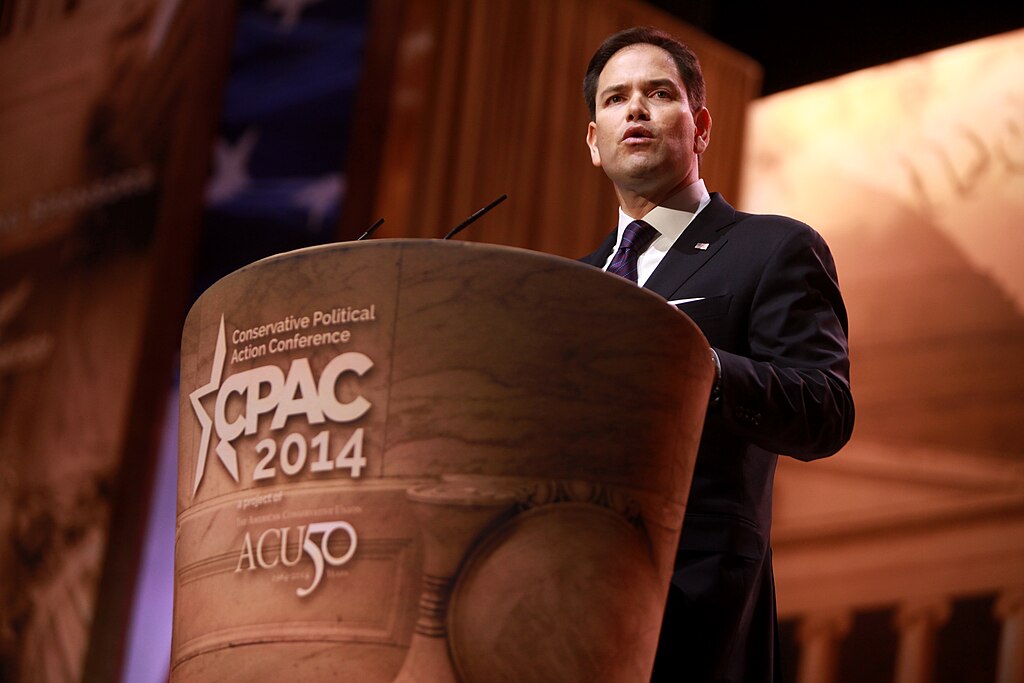

Donald Trump’s nominations in the domain of national security and foreign policy reflect in many ways the diversity of views that characterizes the GOP. The incoming administration’s national security team seems to share a strong sense of loyalty toward Trump. The president-elect’s top foreign policy and national security advisers also share a general foreign policy outlook that is in line with his rhetoric on issues such as China and Ukraine, but more consistent with the GOP’s conventional support for Israel and the government of Benjamin Netanyahu. Representative Mike Waltz, Trump’s choice for National Security Adviser, is a notorious supporter of a confrontational policy toward China; his views concerning the Middle East are also oriented toward a policy of confrontation toward Iran. Marco Rubio, the senior Senator from Florida who has been picked as Secretary of State, is a prominent Republican and is famous for his hawkish stances on Russia, China, and Iran. Trump has selected Pete Hegseth, a popular Fox News host, to run the Department of Defense. Hegseth’s nomination had raised criticism in relation to his lack of administrative experience and his controversial political positions. His worldview seems to be informed by a strong Christian identity defined in contraposition to the Muslim world. Representative Elise Stefanik, Trump’s pick for the post of UN Ambassador, has vocally claimed that the organization is too critical of Israel. Tulsi Gabbard, Trump’s choice for the position Director of National Intelligence, is a former Democrat famous for her anti-interventionist stance, but she has also expressed solidly pro-Israel views. Trump has picked John Ratcliffe to lead the CIA. Ratcliffe is a former Director of National Intelligence and a staunch supporter of Trump. In June, he criticized the Biden administration’s threat to withhold some weapons shipments to Israel. Former governor of Arkansas Mike Huckabee has been asked to serve as Ambassador to Israel. Huckabee is a major exponent of the Republican party’s evangelical base and a staunch supporter of Israel. He has declared that there is “no such thing as a Palestinian” and has openly denied the reality of Israel’s occupation and Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

This overview suggests that the incoming administration’s foreign policy agenda will be dominated by the geopolitical challenge posed by China, but the Middle East will nonetheless be a rather prominent and well-defined item. When it comes to the region, the new Trump foreign policy team seems to be determined to make sure that Washington’s position becomes strongly aligned with that of the government of Benjamin Netanyahu in relation to the war against Hamas, the conflict with Hezbollah, and policy toward Iran. This approach will likely imply a major change in rhetoric compared to the Biden administration, but the substantial change might be less radical, while the reconfiguration of America’s Middle East policy may not be consistent with Trump’s pledge to bring peace to the region or other goals such as managing relations with America’s Arab partners, particularly Saudi Arabia.

Joe Biden entered the White House claiming that under his administration the US relationship with Israel would be “ironclad,” and reiterated this unshakable support for the country in the aftermath of the October 7, 2023 attacks perpetrated by Hamas. At the same time, Biden was a long standing supporter of the Israel-Palestine peace process and recognized the right to statehood for the Palestinians. The Biden administration has expressed major concerns and criticism toward the indiscriminate military response adopted by the Netanyahu government in Gaza. The flow of US military assistance, however, has never been interrupted, and has reached, according to Brown University’s Cost of War Project, $22.76 billion – including direct aid to Israel, the costs of America’s increased military presence in the region, and operations against the Houthis in the Red Sea.

Biden had a notoriously difficult relationship with Netanyahu and his administration was also unpopular in the eyes of Israel’s public opinion. The Israeli prime minister openly supported Trump and the Republicans in the 2024 US presidential race. In spite of the staunch support enjoyed by Netanyahu among Trump’s key foreign policy and national security advisers, however, the president-elect stands out for having criticized Israel’s prime minister for not being prepared for the October 7 attacks. During the presidential campaign Trump also stated that Israel is “absolutely losing the PR war” and argued that the Netanyahu government should “get back to peace and stop killing people.”

During his first presidency, Trump initiated the “Abraham Accords” – a diplomatic process that led to a normalization in relations between Israel and some Arab countries. This policy was continued by the Biden administration but was then interrupted by Israel’s war in Gaza. A continuation of the conflict is a major obstacle to the resumption of this process, and may in particular undermine a rapprochement between Israel and Saudi Arabia – a goal that has been pursued by both Democratic and Republican presidents. Under Trump, the relationship between Washington and Riyadh might be further undermined by Trump’s policy of “Drill, Baby, Drill,” which aims at boosting US fossil fuel production. Such a policy is destined to have severely negative consequences in relation to the global effort to solve the climate crisis, but will probably also push down global oil and gas prices, and thus create serious budgetary challenges for Saudi Arabia. The country is experiencing a significant slowdown in economic growth and is expected to run budget deficits for the next several years. The Saudi government needs an oil price of $96.20 per barrel to balance the budget, but as these lines are written, oil prices barely reach $70 per barrel.

The new Trump presidency will also shrink the chances of reviving negotiations concerning the Iran nuclear program. In 2018, Trump withdrew the US from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (also known as the “Iran nuclear deal”) – an agreement by which Iran committed to allow international monitoring of its nuclear program in return for the gradual lift of economic sanctions imposed on the Tehran regime by the US and the international community. This decision was followed by a policy of “maximum pressure” against the Tehran regime that implied strong economic sanctions and military actions such as the drone strike in Iraq that killed Iranian general Qasem Soleimani in January 2020. Soleimani was the commander of the Tehran regime’s “Quds Force,” and his mission was to provide strategic guidance to pro-Iranian militias that operate in the Middle East, and often carry out attacks against American and allied forces. In the meantime, however, the Iranian government resumed activities such as the enrichment of uranium and made substantial progress along the path toward the capability to build a nuclear bomb. The Biden administration was interested in renegotiating the Iran nuclear deal, but between 2021 and 2024 it proved impossible to reset US-Iranian negotiations. As already mentioned, Trump’s forthcoming foreign policy team shares a very strong aversion toward Iran. Trump’s advisers are inclined to resume “maximum pressure” and even consider military action against Iran. It must be noted, however, that in the summer of 2019, after the Iranians shot down a US surveillance drone, Trump refrained from launching a retaliatory strike that could have led to an escalation in the confrontation between the two countries.

As recalled by Bob Woodward, in 1989, during an interview, Donald Trump explained that “instinct is far more important than any other ingredient.” For better and for worse, instinct appears to have been a crucial component in Trump’s political journey as well. Both his last stint in the White House and his recent presidential campaign suggest that Trump can change his political positions quite easily if his intuition dictates that. “The best deals I’ve made have been deals where I followed my instinct and wouldn’t listen to all of the people that said, ‘there is no way it works,’” Trump told Woodward in the same interview. Instinct may thus be a crucial factor in shaping Trump’s relationship with advisers and foreign partners alike, and may have a decisive impact on the president’s Middle East policy.

Diego Pagliarulo